The Global Vision Deficit: Why Half the World Still Can’t See Clearly

Global Context: The Scale of Challenge

We solve the strategy behind scale!

Refractive errors, including myopia, hyperopia, presbyopia, and astigmatism, have quietly become one of the world’s most widespread yet under-addressed public health challenges. As per the WHO, ~3.4 billion and ~2.1 billion people are estimated to be affected by issues such as myopia and presbyopia, respectively, by the end of the decade. This translates to close to ~4.7 billion people (~55% of the global population) requiring vision correction by FY2030.

The rise is most pronounced across Asia, where rapid urbanisation, digital exposure, and ageing demographics are reshaping visual health. India and Southeast Asia together contribute nearly 30% of the global population affected by refractive errors as of FY 2025, with incidence rates of ~53% and ~65% of the population, respectively. By the end of the decade, India alone is projected to have ~1 billion cases of visual impairment.

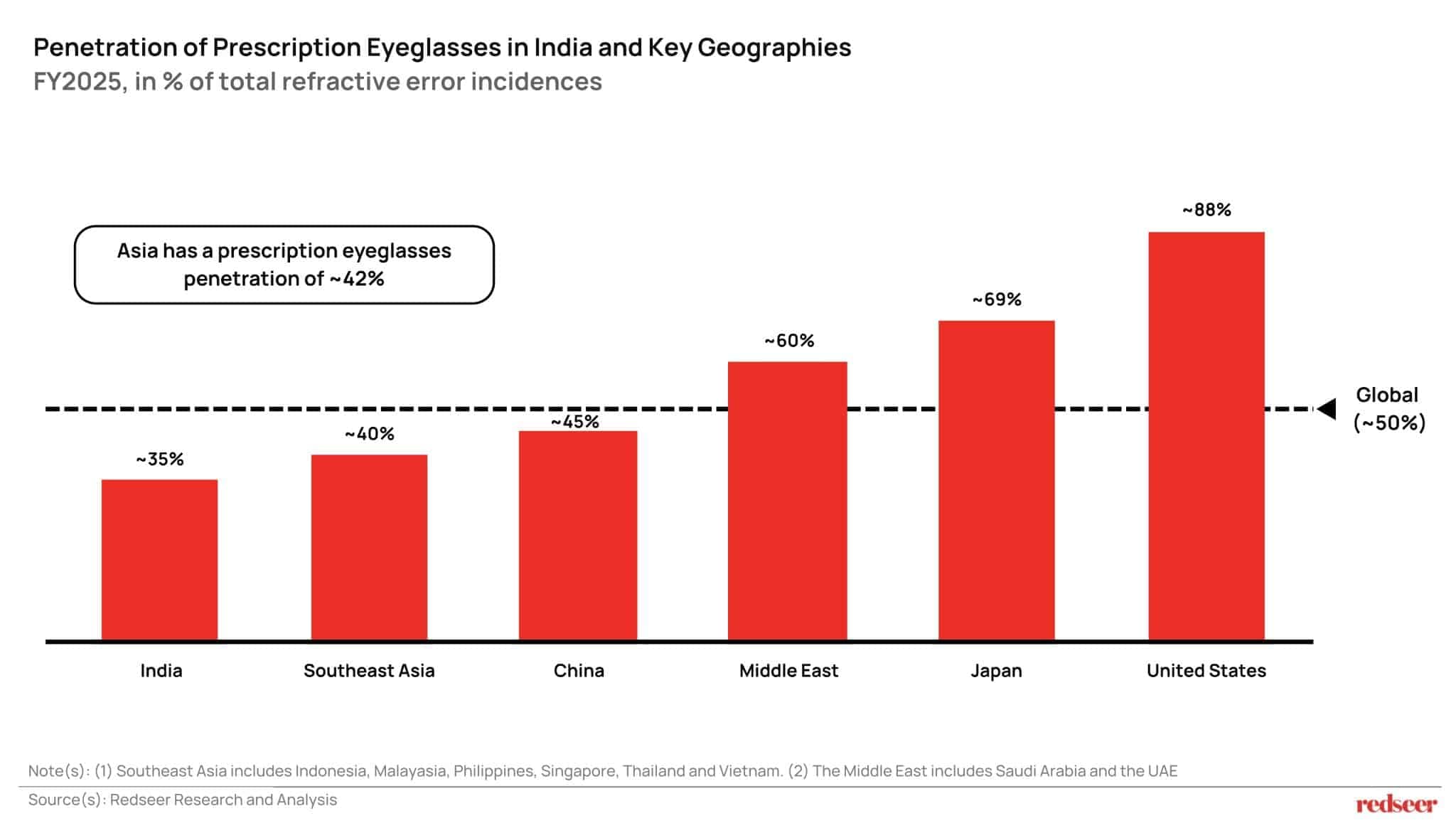

Despite this scale, access to corrective eyewear remains limited. Only ~50% of people worldwide who require vision correction use prescription eyeglasses, leaving nearly two billion people globally without the ability to see clearly.

Seeing the Divide: A Global View of Vision Inequality

Vision inequality has become an invisible fault line running through global development.

In high-income markets such as the United States and Japan, penetration levels of prescription eyewear are estimated at ~88% and ~69%, respectively: the result of mature healthcare ecosystems, regular screening, and organised optical infrastructure.

In contrast, much of Asia remains underserved. India’s penetration stands at ~35%, Southeast Asia at ~40%, and even relatively prosperous Middle Eastern markets hover near 60%. These disparities are amplified by the absence of insurance coverage for eye care and the high out-of-pocket share of household health expenditure.

Even within India, the inequality is layered. Penetration in metros is around 53%, while in Tier-2 and smaller towns it falls to roughly 32%. The difference is not just infrastructural: it reflects the deeper gap in awareness and affordability that continues to limit access to vision correction.

In many developing economies, being able to see clearly is not yet a universal right. It remains a privilege: one that depends on income, geography, and access to care.

Why India and Southeast Asia can’t see clearly

The reasons driving low penetration are more structural than clinical and are not unique to India.

- Firstly, awareness and consumer behaviour are reactive. In many markets, screening typically happens only when impairment becomes obvious. Social perceptions can delay first-time testing and adoption. This reactive pathway is a key reason for low conversion from need to usage in India and emerging Southeast Asian economies, in contrast to geographies such as Japan or Singapore, where regular testing is the norm.

- Secondly, professional capacity is thin. The World Council of Optometry recommends 100 optometrists per million people as a benchmark. Southeast Asia has 30-45, while India has 35-50 per million, and the Middle East has 60-70, therefore creating the need for solutions such as remote/tele-optometry and policy efforts to stretch limited capacity.

- Thirdly, the distribution footprint is shallow. India has ~60 optical stores per million people – far lower than essential retail formats like pharmacy or electronics, which routinely exceed 350–1,000 per million. Limited last-mile access, high setup costs for diagnostic equipment, and shortages of skilled staff keep physical capacity tight.

- Fourthly, affordability remains a stretch. Entry-level single-vision eyeglasses in India retail under ~₹1,500, while progressives under ~₹3,000; luxury options exceed ~₹8,600. Emerging Southeast Asia shows similar thresholds. For lower-income households across these emerging markets, even the entry price can be a meaningful share of monthly earnings.

- Finally, supply-chain structure elevates end prices. Concentrated global lens manufacturing, import dependency for frames, multiple intermediaries, and the requirement for skilled labour in edging and fitting cumulatively raise costs and create variability in experience, further depressing conversion from diagnosis to purchase.

The Socioeconomic Cost of Uncorrected Vision Impairment

Uncorrected refractive errors carry significant productivity and economic implications. In labour-intensive sectors, refractive issues among workers could lower worker efficiency, raise error rates, and increase risks to safety. As per the WHO, every year, uncorrected vision issues lead to an estimated USD 250 billion in losses. Asia accounts for over half of that loss, and India’s annual economic loss alone is nearly USD 30-45 billion of this. While these losses are concentrated in labour-intensive sectors where visual acuity is directly tied to output and safety, they propagate into education, household earnings, and long-term health costs.

The striking contrast here is between the scale of loss and the simplicity of remedy. A basic eye test and an affordable pair of glasses can restore productivity in days. The ROI on vision correction, measured in learning outcomes, employability, and avoided medical costs, is significantly high for a population-scale intervention.

The Decade of Vision: How organised players are widening access

Across major emerging markets, eyewear is beginning to shift from a fragmented, low-awareness category into a coordinated ecosystem that reaches people wherever they are.

The most visible progress is coming from organised retailers who combine technology, scale, and service standardisation to address the long-standing barriers of awareness, access, and affordability. Vertically integrated sourcing and local assembly have reduced manufacturing and distribution costs. By cutting intermediary margins and shortening supply chains, these players have been able to offer high-quality eyewear at accessible price points, turning what was once a periodic expense into a manageable household purchase. Technology has further amplified this impact: mobile eye-testing vans, virtual try-on tools, and AI-driven lens recommendations are simplifying what used to be a cumbersome experience.

What makes these efforts transformative is their compounding effect. Every first-time wearer added to the system represents more than a retail transaction: it is a productivity gain, a safer commute, a child who can finally read the board. The momentum building within organised retail, therefore, sits at the intersection of business growth and social progress.

Discover the right strategies and market opportunities. Talk to our experts to solve for your next growth milestone.

More than half the population that needs vision correction still doesn’t have it: often because of awareness or affordability. Correcting this isn’t just good business, it’s a social multiplier. Every pair of glasses given to a first-time wearer expands their ability to learn, earn, and live with confidence. In that sense, vision correction sits closer to the base of Maslow’s pyramid – but it enables everything above it.

– Rohan Agarwal, Partner, Redseer

Written by

Rohan Agarwal

Partner

Rohan Agarwal has been a part of the Redseer Strategy Consultants journey for over six years. He is an expert in digital strategy for traditional corporates and start-ups.

Talk to me