Dubai: Jeff Bezos met top film stars, Shahrukh Khan being among them, and made promises of spending $1 billion in India to take the Amazon story forward.

But it is who he did not meet during his high-wattage visit to India that could have far-reaching consequences for Amazon — in what has become an exceptionally important market for the e-retailer.

Despite speculation he might, Bezos never had a face-to-face with the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Neither did he come across Mukesh Ambani, India’s wealthiest man, who is currently scripting Reliance’s take-no-prisoners push into the world of online buying and selling. (Bezos, in fact, has never been off the headlines in these two weeks, with the latest one related to Saudi Arabia.)

As for meeting Modi, it could have proved an embarrassment for both as India had just announced an investigation into Amazon and Flipkart, on whether the two marketplace giants were offering heavy discounts to gain competitive advantages. (Flipkart, now owned by US retail giant Walmart, is the other leading player in India’s ecommerce space.)

A meeting would not have gone down well politically within India as well — right from the moment Bezos landed in India, he was met with protests from small-scale retailers, who still retain an outsized influence in society, and are concerned that Amazon is doing everything to put them out of business.

This is also a base that the ruling BJP-led government would not want to displease, given that they represent some of the party’s most ardent long-term supporters.

For India’s online shopping universe, these are proving distractions to what has essentially been high-octane growth — and more of it — in recent years.

Which is why market watchers are hoping that the Indian government would go in for a broad re-write of its e-commerce policy.

“The existing policy has imposed numerous restrictions over the marketplaces — Amazon and Flipkart,” said Anuj Puri, chairman of Anarock Property Consultants. “India’s ecommerce companies have been struggling to balance operations and profitability.

“More than fresh restrictions, what the e-commerce sector needs is a comprehensive policy and guidelines from the forthcoming budget (due on February 1). Stakeholders expect the government to take steps to improve consumption and spending while simplifying GST (Goods and service Tax) for online vendors and bringing more parity with their offline counterparts.”

Tough to act

But would the government have the political will to make this happen, especially at a time when the economy is slipping into a low-growth freeze. It would take a lot of guts to do anything that might be construed as giving ecommerce players a boost while the brick-and-mortar retailers are facing the worst crisis of confidence in nearly a decade.

And it was as recently as December 2018 that the government restrained online giants from selling products of companies in which they have a stake. According to the circular, these businesses were also barred from exclusive arrangements with sellers and offering steep discounts to consumers.

“The new rules clarified that foreign direct investment would only be allowed in e-commerce companies that provide marketplaces for buyers and sellers,” said Puri. “These restrictions have forced online majors to rethink their business models and look for alternative sources and business arrangements.” (To comply with the new rules, Amazon sold its stake in Cloudtail, an Indian online retailer.)

Now comes the investigation into whether Amazon and Flipkart had breached these requirements, especially in offering steep discounts.

A billion-dollar game

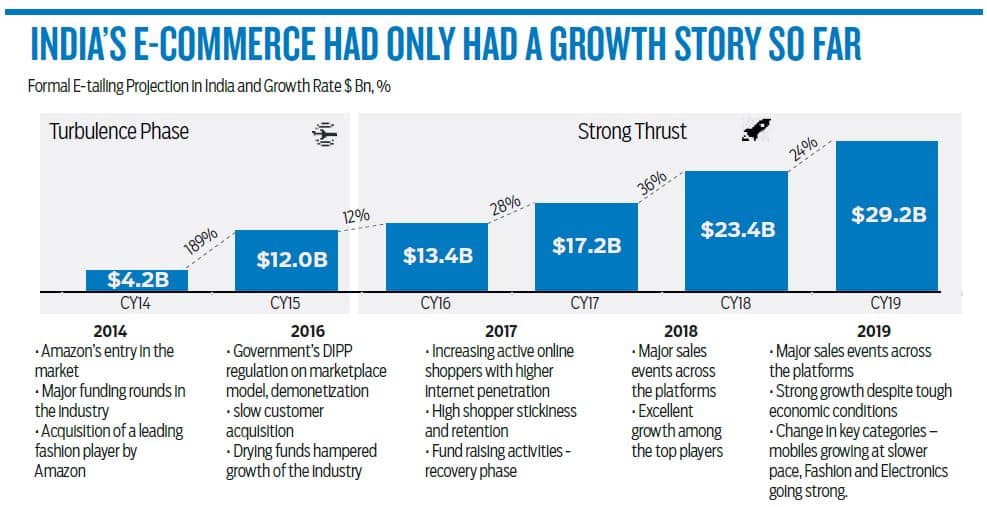

Despite the political headwinds, Bezos was on a charm offensive all through the India visit. With solid reason too, given the billions that are at stake. According to RedSeer Consulting, India’s e-shopping touched $29 billion (Dh106 billion) last year from $23 billion the previous year.

During a six-day period marking “Diwali”, Amazon and Flipkart pulled in just over $3 billion worth of orders.

“This growth despite a slowdown in overall retail spending showcases the resilience – and maturity – of the industry,” said Sandeep Ganediwalla, managing partner at RedSeer.

“Electronics and fashion categories saw a breakthrough year with cumulative 30 per cent growth year-on-year, driven by strong performances of marketplaces as well as “super-vertical” players in the category.” (Super-vertical refers to those online portals that specialise only in one product category, while marketplaces such as Amazon offer just about everything under the sun.)

The whole of India is joining in the online shopping party and not just the city dwellers. It could also be why small retailers are particularly concerned about the Amazon onslaught.

“While the number of shoppers in metro-cities are growing at 10 per cent plus, in Tier-2 cities, online is growing at 25 per cent year-on-year,” Ganediwalla added. “But profitability in India’s e-shopping is at least three to five years away.”

And then comes Reliance

Profitability or not, the biggest influence on industry-wide fortunes would be when Ambani’s Reliance decides to go full tilt into online. It already has the bare foundations to make things happen.

“With the unveiling of JioMart, millions of neighbourhood stores are expected to be linked to the millions of customers of Reliance’s 4G telecom network Jio,” said Puri. “For this online venture to give stiff competition to existing players, it will have to offer discounts, cashless payment, in-store credit and the convenience of home delivery.

“It’s anybody’s guess whether this new venture will be a formidable play – but it will surely shake up the market and make way for some serious churning.”

When Mukesh Ambani is part of the equation, it won’t be anything less than a complete churn.

For Bezos, becoming a more frequent flier to India would make sense. The final word is yet to be said in the world of online shopping in India.

Slow going for brick-and-mortar

A slowing economy is being felt across all of India’s real estate verticals, including retail leasing. Leasing of retail space in India’s Top 7 cities dropped 35 per cent in 2019 over 2018 – from 510,000 square metres (5.5 million square feet) to 335,000 sqm (3.6 million square feet).

“The threat of slowdown is a reality that has hit the retail industry as well,” said Anuj Puri of Anarock. “For an industry dependent heavily on consumption and spending, the dropping GDP growth rate is having visible repercussions.”