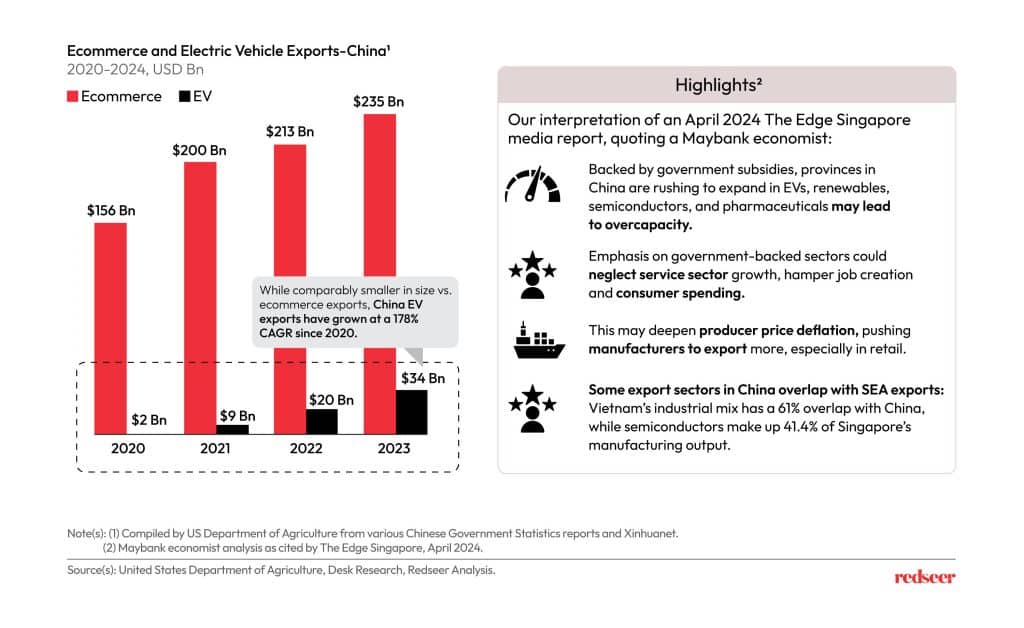

Headlines as of late have been dominated by China’s historic push to develop high-tech manufacturing. The Chinese government is bullish on electric vehicles (EV), semiconductors, and renewables—building nationwide capacity with the aim of becoming a dominant global player.

However, according to The Edge Singapore commentary, China’s gargantuan capacity-building efforts could lead to overcapacity, while its strong export figures could be indicators of a sluggish domestic economy.

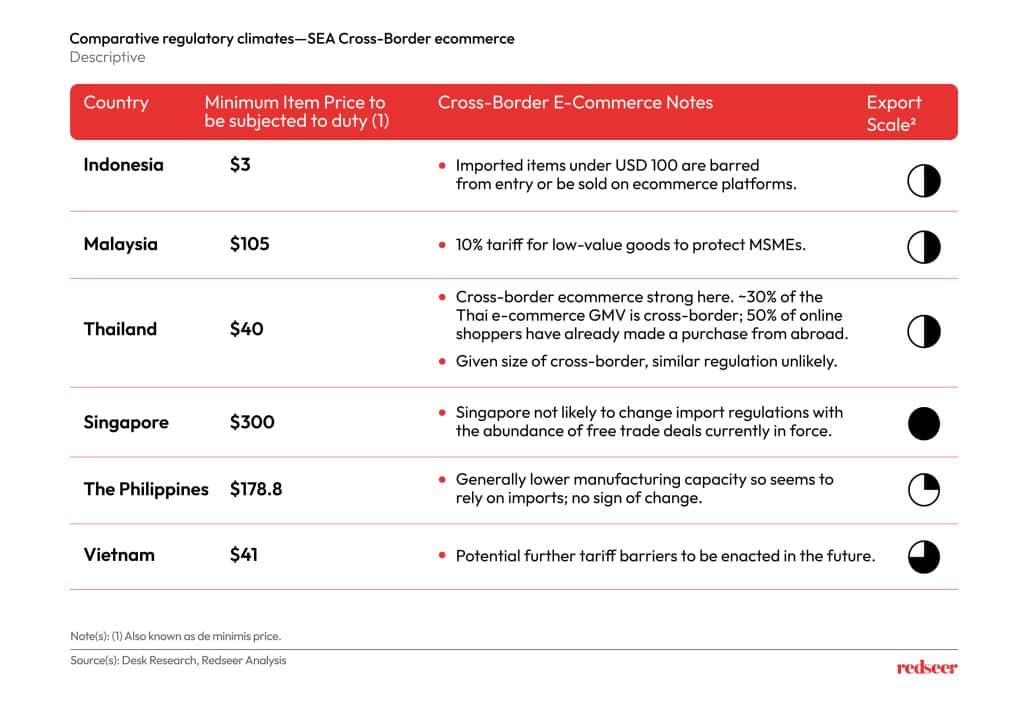

China’s strong export trends caused some countries with overlapping sectors to enact measures to protect local businesses. In the US, the Biden Administration has recently enacted a 100% tariff on EV imports from China. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia have enacted restrictions and tariffs for low-value goods imported through e-commerce to maintain the competitiveness of their MSMEs—something we will touch upon later in this article.

Faced with these policy trends and shifting regulatory landscapes, how could businesses optimize further opportunities in Southeast Asia?

1. Chinese e-commerce exports have nearly doubled in the past several years—but numbers suggest a slowing internal market and, a need for export.

In an article titled Asean exporters’ recovery facing growing and multi-faceted competition from China: Maybank, The Edge Singapore, quoting Maybank, states that China’s push for certain sectors such as EV, renewables, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals could result in overexpansion that could compromise the growth of the service sector—the leading generator of jobs—and in turn, private consumption.

Lower domestic private consumption may push manufacturers to increasingly rely on exporting. Manufacturers in other sectors such as retail fashion and appliances, having highly adopted cross-border e-commerce platforms, might have to seek a larger share of growth in other regions such as Southeast Asia.

The same article asserts that high-tech manufactured goods from China could also come into overlap with Southeast Asia’s industrial mix. 61% of Vietnam’s industrial mix overlaps with that of China, while Singapore has a 60% overlap due to its high-tech manufacturing output. China’s high-tech policies might potentially come in contest with Singapore’s semiconductor and pharmaceutical production, respectively being ~41% and 5% of the country’s total manufacturing output.

The phenomenal growth of China’s EV exports, having grown ~178% CAGR between 2020 and 2023, could be seen as an example.

RENEWABLES SECTOR

Having set out annual commitments to reduce carbon-based energy sources such as coal, the Indonesian government is poised to raise foreign and domestic capital for renewables-based power projects. However, key legislation—the New & Renewable Energy Bill—remains in limbo.

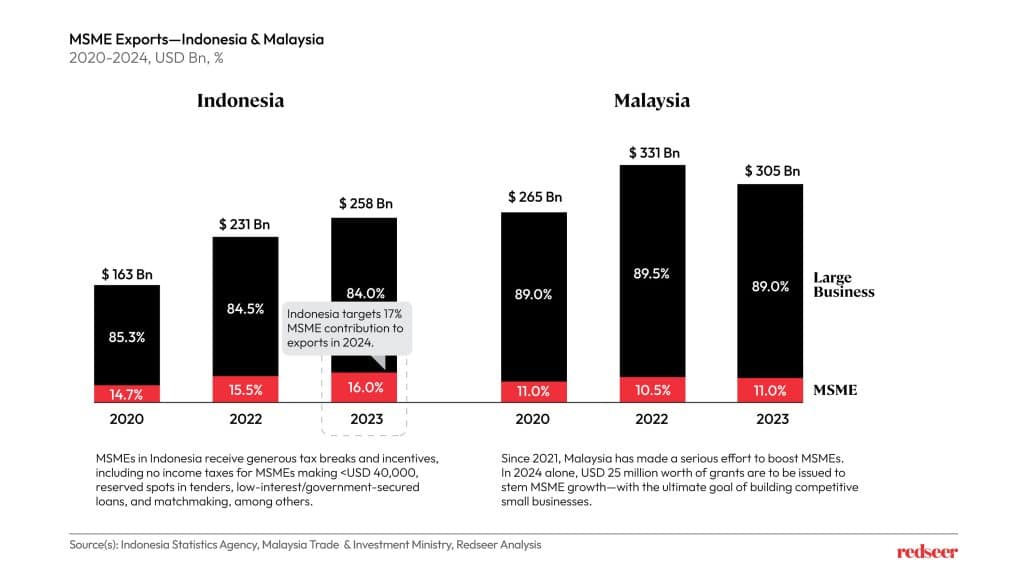

2. One key area of overlap in Southeast Asia is in low-value goods such as fashion, and home appliances that are exported by China through e-commerce – clashing with Indonesia and Malaysia’s MSME push

Similarly, cross-border e-commerce sellers from China—selling goods from fashion to beauty products—are overlapping with Southeast Asia’s MSMEs. This comes at a time when countries like Malaysia and Indonesia are building the capacity and competitiveness of their MSMEs.

In Indonesia, MSME growth and development have been a major component in economic policy. Starting off from government-secured, low-interest loans (Kredit Usaha Rakyat), MSMEs are further supported with digitalization support, workshops, matchmaking, and generous tax breaks. Similarly, Malaysia has been growing MSME’s capabilities with government grants among other measures.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, certain measures have been enacted to increase the competitiveness of local MSMEs.

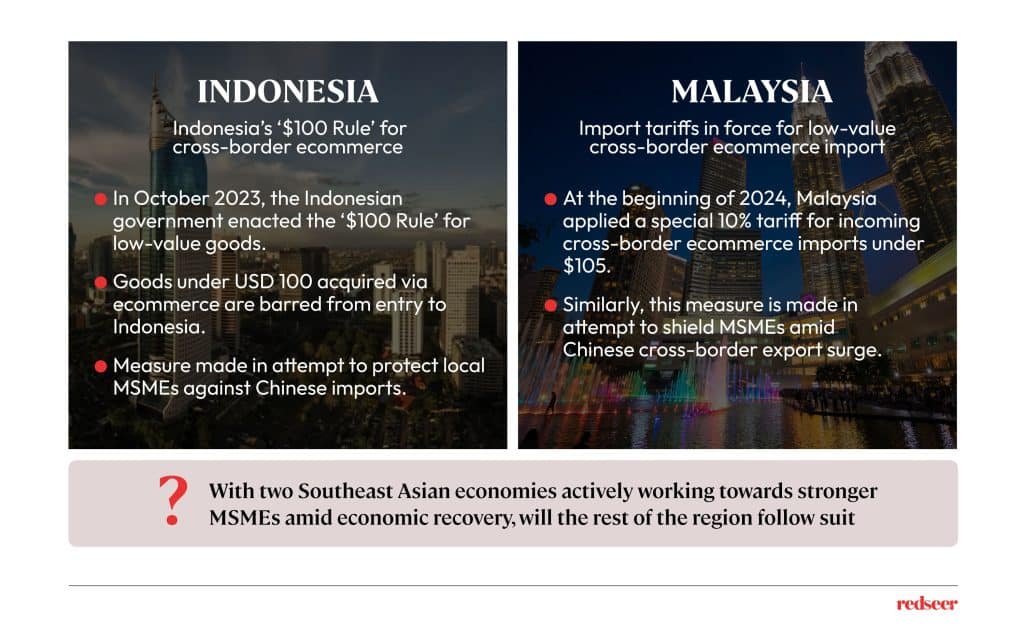

3. Indonesia and Malaysia have enacted policies to maintain the competitiveness of MSMEs and control cross-border e-commerce imports

The intensifying adoption of e-commerce by small businesses in Indonesia and Malaysia puts them in direct competition with importers who sell on e-commerce platforms—and as is the case with China-based sellers, with extremely competitive prices.

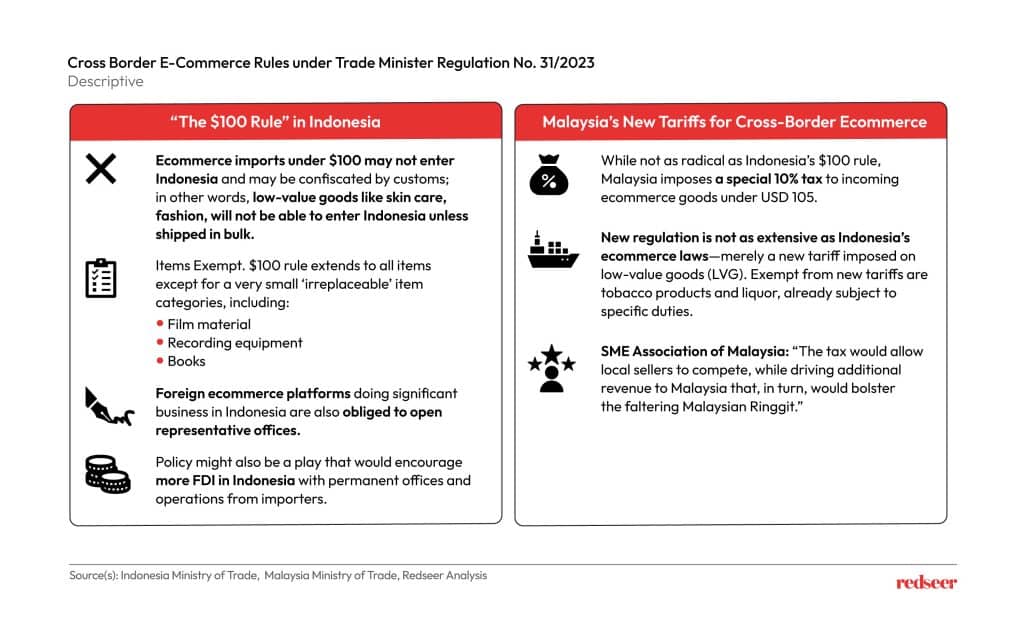

In October last year (followed up by a December update), the Trade Ministry of Indonesia issued Regulation No. 31/2023, which suspended social commerce plays like TikTok Shop but also enacted a USD 100 minimum item value for e-commerce imports.

Similarly, earlier this year, Malaysia followed suit in imposing a 10% tariff on imported goods acquired online under USD 105.

Indonesia’s USD 100 minimum item value for e-commerce imports and Malaysia’s 10% special tax for imported goods acquired online under USD 105 was the first policies of its kind in Southeast Asia.

4. The ‘$100 Rule:’ In response to MSME export woes, the Indonesian government implemented a policy that limits small-value e-commerce imports to support MSMEs

Malaysia’s new tariffs are in no way as extensive as Indonesia’s e-commerce regulations—which actively promote aggregation, registration, and foreign investment. In Malaysia, reception is mixed; but the new policy does provide an additional incentive for Malaysians to ‘buy local’. On the other hand, SME leaders in Malaysia have applauded the new measure, seeing it as leveling the playing ground for local companies and SMEs.

5. Indonesia and Malaysia take on e-commerce imports—but seeing the same external challenges, will other countries follow?

After analyzing the regulatory stances of other Southeast Asian countries on cross-border, we can deduce several directional conclusions:

- While low-value goods are faced with restrictions, importers would opt to ‘set up shop’ in-country both through direct investment, franchising, or distribution rights arrangements, not too dissimilar from a few China-based F&B and Beauty players finding success in Indonesia.

- Collaborative competition such as aggregation for high demand and popular imported products with local partners.

- Encourages consumers/businesses to buy in bulk over piecemeal items.

Stay tuned for more Southeast Asia policy updates—subscribe to our newsletter today.